“Well, I don’t know.” Anne looked thoughtful. “I read in a book once that a rose by any other name would smell as sweet, but I’ve never been able to believe it. I don’t believe a rose would be as nice if it was called a thistle or a skunk cabbage.” (L.M. Montgomery, Anne of Green Gables, Ch. 5)

Shakespeare would rightly note that an archival pigment print by any other name is still an archival pigment print. While Sartre just might point out that the name archival pigment print just confuses things. On the other hand, Sinatra would still say, “do be do be do be do-wah”. It all goes to show that whether Murakami attaches the moniker “archival pigment”, “giclée”, or even simply, “inkjet”, collectors will still line up and pay thousands of dollars to get his eponymous John Hancock on a colored sheet of Canson Velin cotton rag paper with deckled edges.

With respect to Murakami’s latest output, last year’s installment on Murakami hanga, It’s Silkscreens All the Way Down, perhaps overemphasized the rarity and quality of Murakami handmade hanga compared to his machine creations, whilst ignoring his larger history of Xerography, and completely failing to anticipate his business-instinct to reduce the use of labor at all costs. Now with a warm plate of crow sitting on fine porcelain china as one might find on the dinner-table of Muriel Spark’s Miss Pinkerton, Sugimoto68 must clear its throat to provide a revisionist account of the rarity and exquisite beauty of the Murakami Takashi low edition number mechanically generated print.

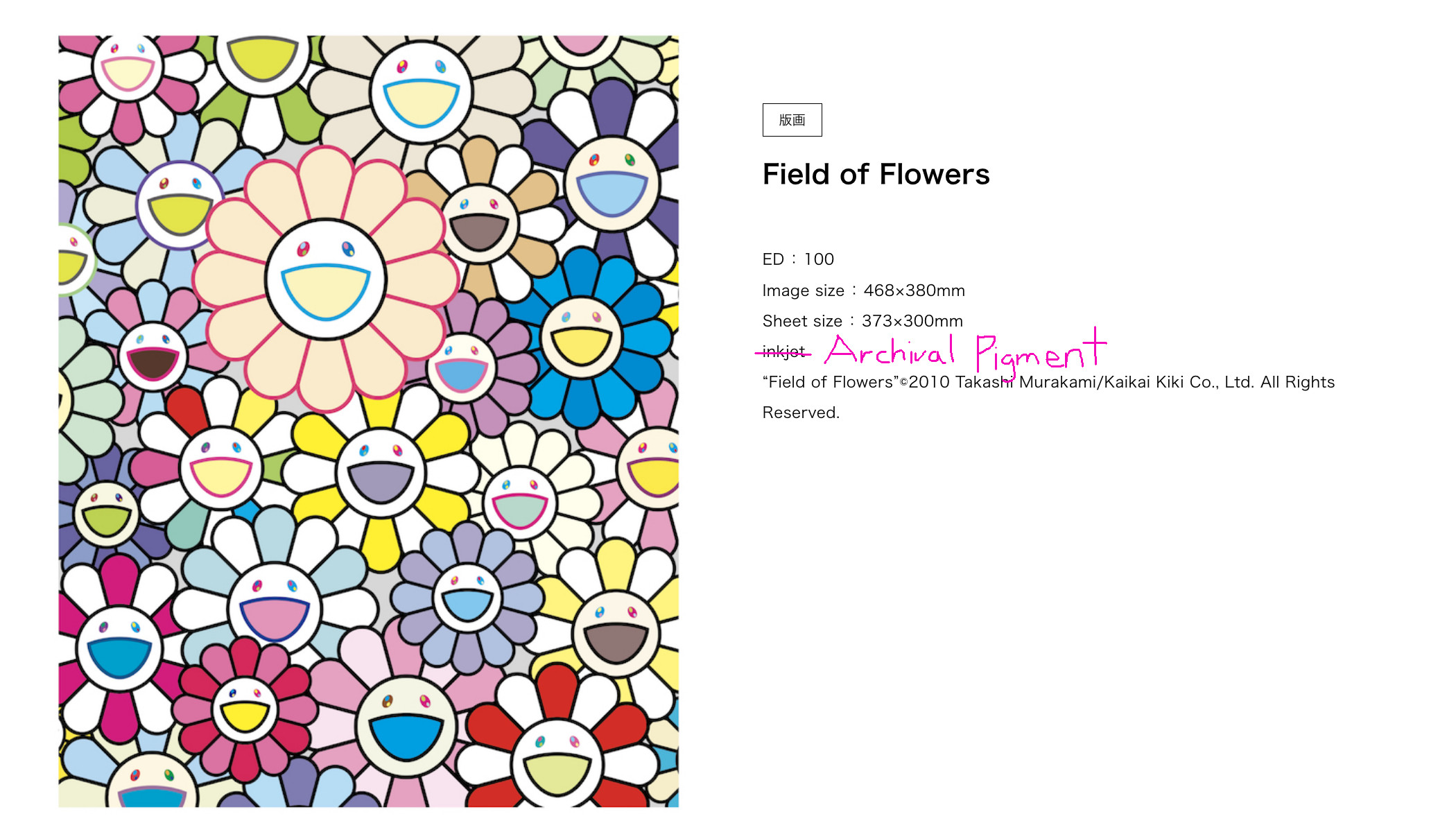

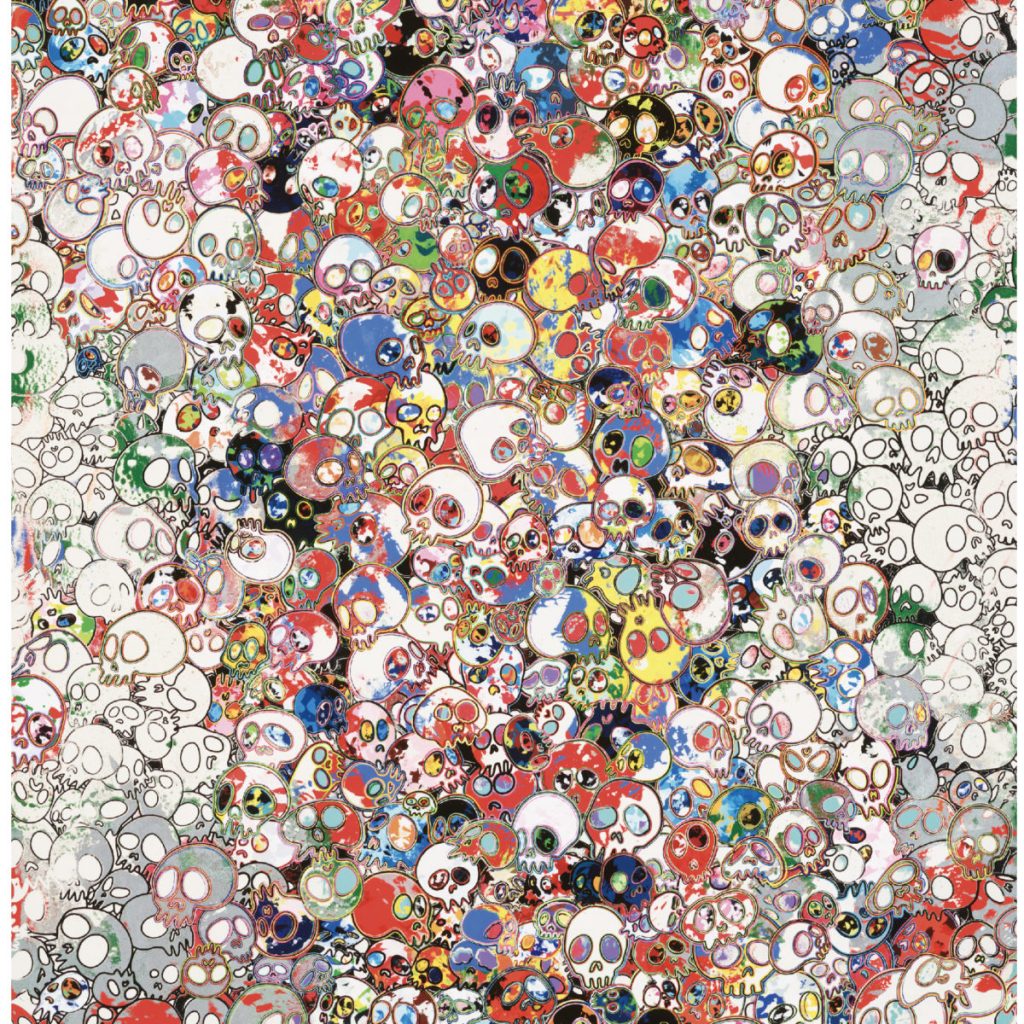

Murakami’s rather audacious turn introduces a series of “archival pigment” editions of 100, Field of Flowers, Flowers of Hope, A Fork in the Road, and an untitled print adorned with the ubiquitous Murakami skulls drenched in crimson-red archival pigmentation. As pointed out repeatedly––by completely objective artists and dealers––these are extraordinarily high quality prints created in low numbers by a professional-grade inkjet printer that vividly transfers the original concept from the mind of the artist directly to the cotton vellum as much as any printing process can––and they will be enjoyed for generations. While many collectors obsess over them, a group of grumpy naysayers see such prints as overblown mechanical reproductions that lack the purity of a print pulled personally by the hand of the anguished, overworked, and undercompensated Auteur’s assistants. Well now Sugimoto68 will show you how to have your cake and Marie Antoinette too.

A Brief History of Murakami’s Xerography

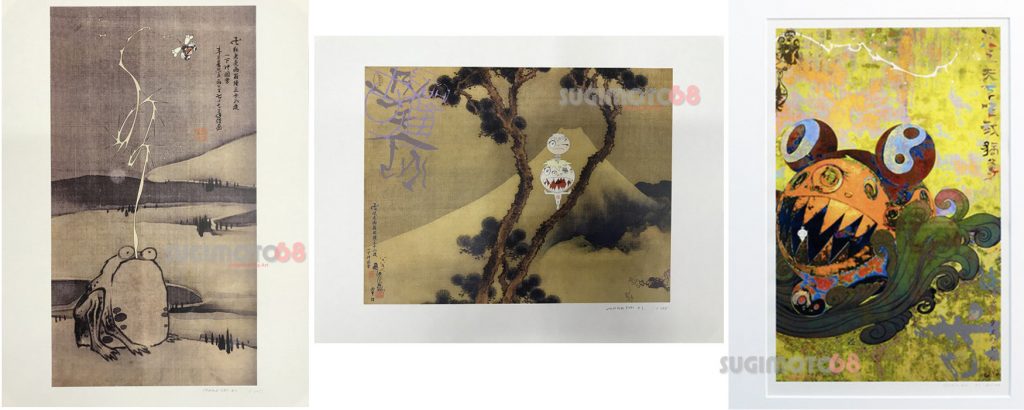

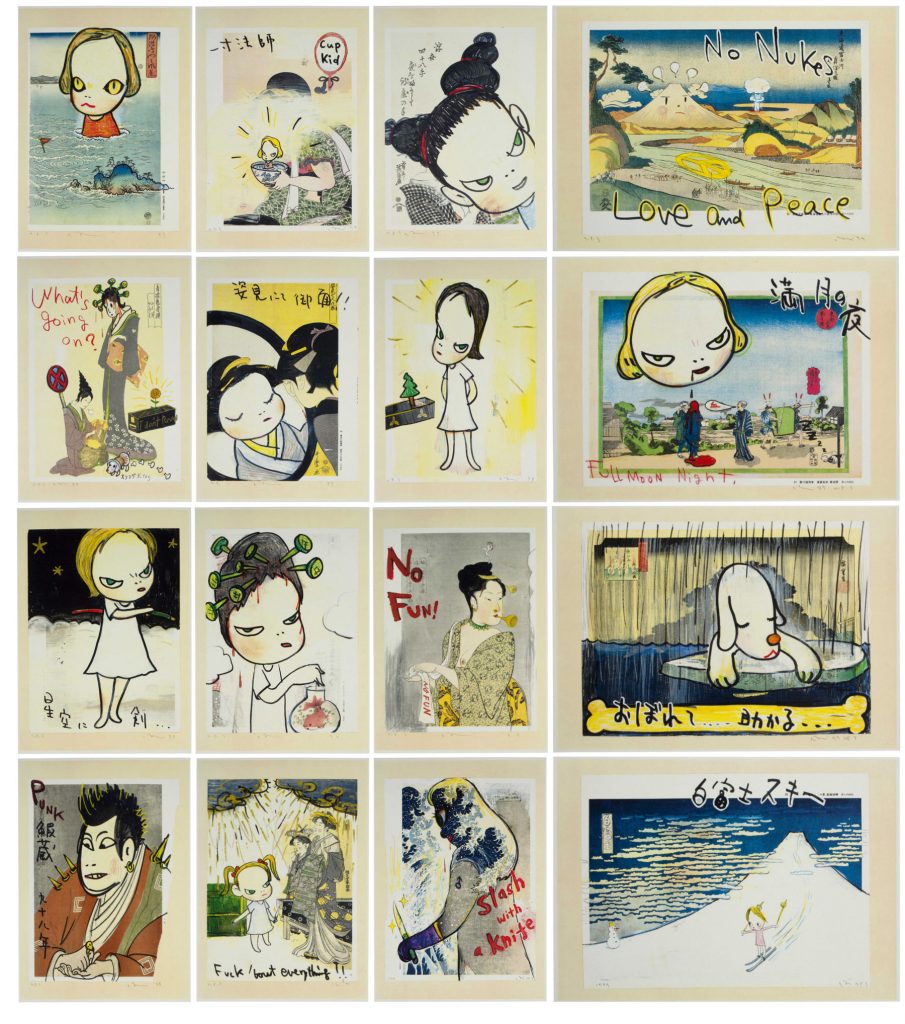

This is not Murakami’s first flirtation with the use of mechanical technology for hanga; early in his career he produced three color laser Xerox editions in 2001: Manji-Fuji, Kerotan and 72727 (Prints and Why I Love Them, pp 12-14). As we and Wikipedia all know, the Xerox art print has been around since the 60s and was big in the wild hippy-dippy San Francisco art scene in the 70s. Warhol also applied this technique to some extent, which explains where that copycat Murakami derived the concept of transforming a mundane mass produced sheet of paper into money. Interestingly, two years earlier Yoshitomo Nara in his In the Floating World series also used a Xerox to produce his early limited edition series, so maybe the copycat is copying a copycat who was inspired by a cat copying. Aesthetically speaking, Nara’s prints preserve the child-like crayola scrawl of his original creations while Murakami’s prints have a sort of light meshy backdrop with a canvas feel. Pragmatically speaking, the Xerox machine allowed poor middle-aged artists living in their friends’ basements a way to produce “collectors items”.

They’re back ¥¥

Now 20 years later, Murakami returns to the scene with a new machine processed hanga, so now we can rejoice in a high quality Murakami hanga at a low, low overhead for Murakami. While an inkjet is expensive to produce compared with an offset print, Murakami’s latest Flower prints each have an eye-popping 163,000 yen retail price tag. Compared with the same sized handmade silkscreen Little Flower Painting prints (2018), the price has doubled. A Fork in the Road at 220,000 yen seems more reasonable for its larger size; however the untitled skulls print has a rake-in-the-face slapping 500,000 yen price tag, more expensive than many of his larger, more intricate handmade silkscreens. The overwhelming question on everyone’s and Wikipedia’s mind is, what makes these archival pigment prints just as, or more dear than Murakami silkscreens? Well just hold my Miller Lite beer a second.

What’s in the box?

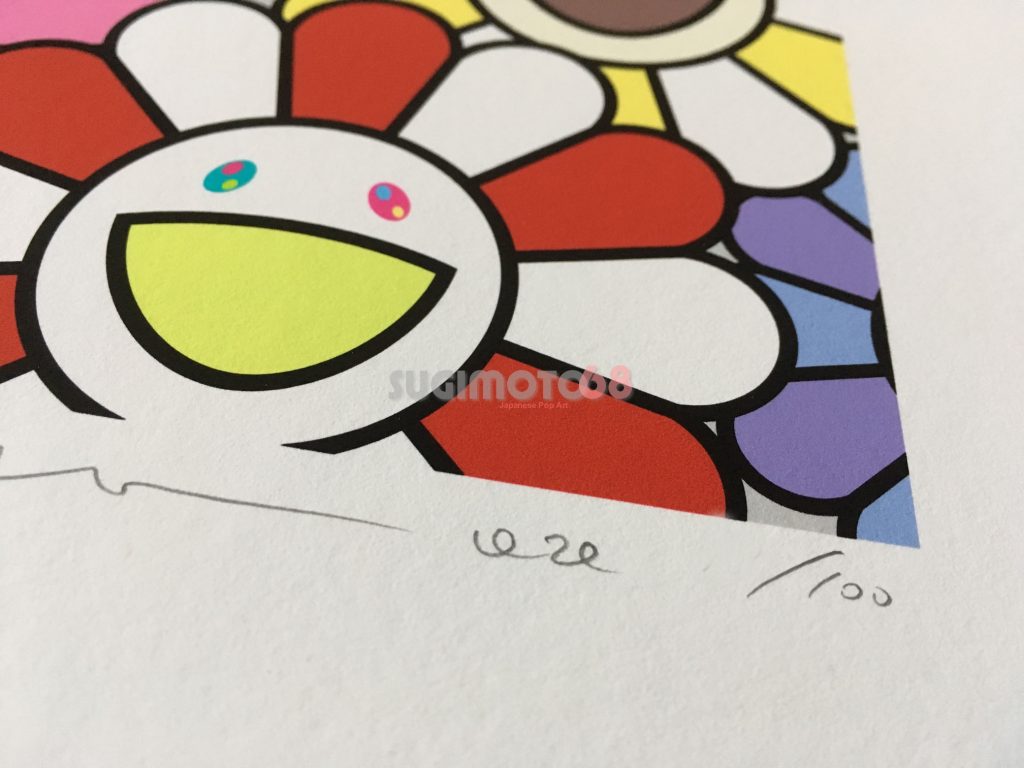

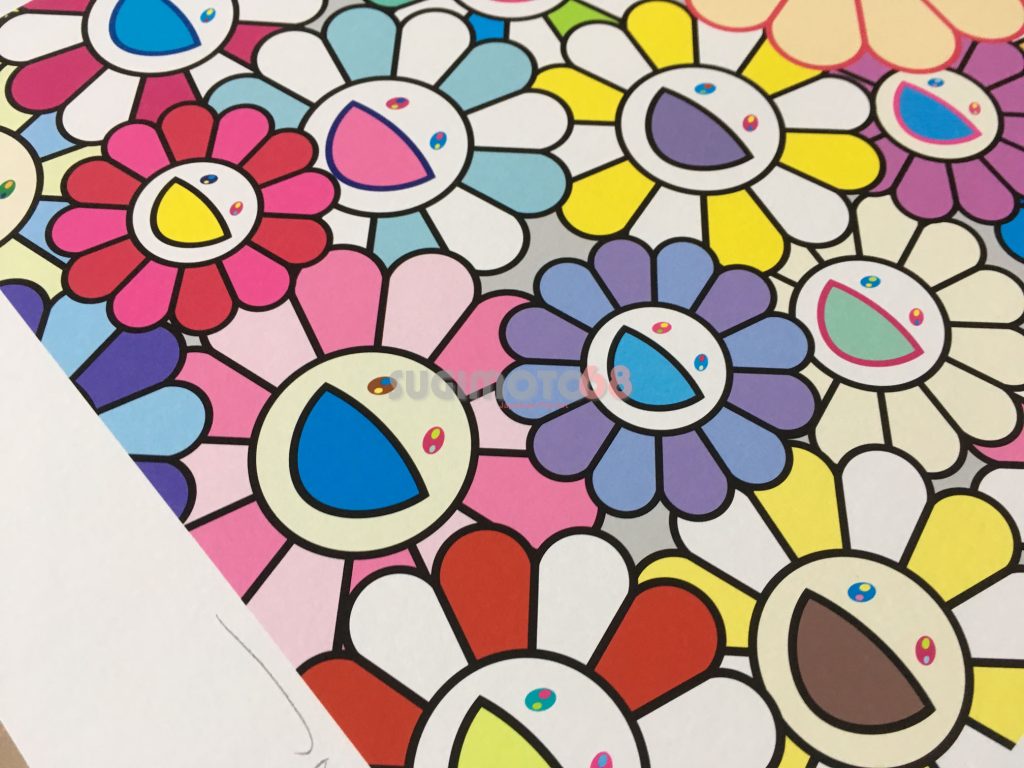

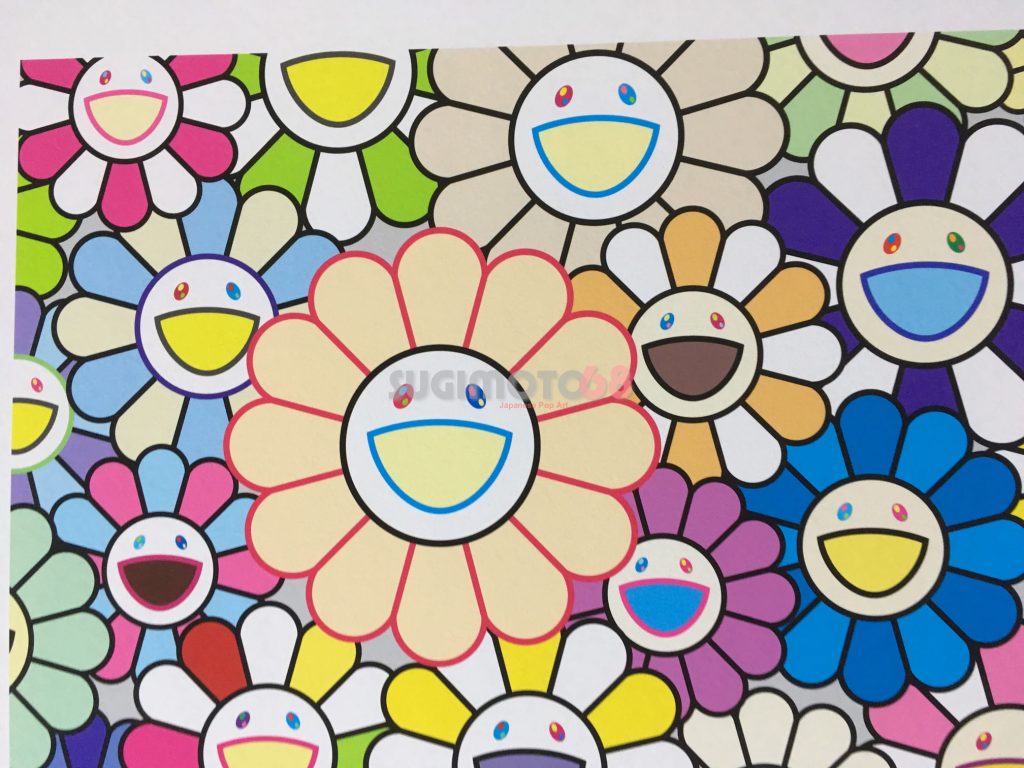

Enthusiastic collectors, skeptical investors (begrudgingly), and even money-grubbing dealers, would all agree that aesthetics are paramount to an art piece. From the pictures, we can see that Murakami has spared no mark-up expense to conceive the finest print producible.

1 The Wonders of Technology!

The superb archival pigment Flowers of Hope print has colors rich, smooth and silky as a baby’s bottom, whereas the Little Flower Painting silkscreen up-close resembles a pockmarked golf ball with acne. The Field of Flowers and Flowers of Hope print design is not the byproduct of some mere room full of monkeys, but a precise interpretation that transfers the pure artistic concept from the mind of Murakami the Auteur, unsullied by the hands of overpaid lackeys, to the fine Canson Velin cotton rag paper. Look at those vibrant, lively colors! Look at those clean, precise lines! Squint and look at those deckled edges!!

2 Oh! The Wonders of John Henry!

But on the other hand, the wonderful traditionally hand-crafted Little Flower Painting silkscreen displays the delicate traces composed by the artist assistants’ own hands. The porous richness of the carefully layered inks visible to the closely-observant naked eye, painstakingly aligned, infuses the work with a creative by-the-sweat-of-my-brow essence, comparatively lacking in the cold, flat archival pigment colors unemotionally churned out by the soulless EPSON Stylus PRO 11880 or equivalent.

The choice?

You would think that it comes down to whether you are on the side of humans or machines, but our existence is not mutually exclusive. Open your bitcoin wallets, bank accounts, credit cards, and mortgages wide, to find a place for both types of prints in your heart and over your hearth. Or in the words of Sinatra, “do-be, do-be, do-be, do-waah”!

Gratefully inspired by the verbal manipulations of Johnathan Goldstein’s Heavyweight

The title is with reference to Dave Sim‘s Cerebus #102

Gratuitous pictures of Field of Flowers of Hope